Why does Brattleboro have Representative Town Meeting? Why not a regular, open Town Meeting like the rest of Vermont? These questions led me on a search through old newspapers and town records to look at Brattleboro’s town meetings in the 1950’s to see if there was some obvious answer.

It turns out, there was no single reason that led to the “representative form of government” in Brattleboro. There were many factors, personalities, and coincidences unique to Brattleboro that contributed to its adoption.

Arguments made in favor of representative town meeting were sometimes specific to Brattleboro, such as outgrowing the public meeting hall. Other times they were more lofty, arguing that representative government would be more fair and better able to deal with complex issues, while giving voters a greater say in how the town operates.

It isn’t clear how much voters knew about the new system when it was first adopted, but the town quickly divided into supporters and opponents of the representative form of government after it was in operation. That division has remained to this day, as do questions of how well it works.

This story is in two parts. The first will examine the years leading to the adoption of Representative Town Meeting; the second will look at the post-adoption reaction and the temporary repeal of representative town government.

Local Issues and Changing Times in the 1950s

Brattleboro in the 1950s was beginning to experience both the challenges of post-war middle class growth and the associated costs and consequences. Population-wise, Brattleboro was on the big side of being a town, but remained a bit too small to become a full-fledged city. Stuck in the middle, citizens worked through new issues they faced using their traditional form of governing, the open town meeting.

Brattleboro in the 1950s was beginning to experience both the challenges of post-war middle class growth and the associated costs and consequences. Population-wise, Brattleboro was on the big side of being a town, but remained a bit too small to become a full-fledged city. Stuck in the middle, citizens worked through new issues they faced using their traditional form of governing, the open town meeting.

There was a boom in the number of cars after the war. Many meetings were spent discussing parking issues, creating plans for parking, and buying up land in town to create parking lots. Harmony Lot, for example, was the focus of many discussions and business meetings.

Selectboard meetings often began with the granting (or limiting) of taxi licenses for the numerous taxi services in town. One meeting, for example, helped sort out where each of the four major cab companies could stand to pick up passengers. Another was to discuss a rate change of 25 cents to 50 cents per trip.

The town’s tax system was being looked at, and it is during the 1950’s that the Vermont Legislature enacted the optional Local Option Taxes for towns in the state. Homeowners came to meetings to discuss the way their property was being assessed. Brattleboro needed to start doing something about garbage pickup and sewage treatment.

The 1950’s saw other improvements such as a new fire station, new high school, raising the water reservoir dam, a 16-inch water main, taking ownership of Living Memorial Park, a new swimming pool, and paving and street improvements.

Brattleboro voted to join a union high school district to share costs with neighboring towns. Town Meeting members voted to spend money to renovate the old high school to become our new Municipal Center.

Chief Mattison recommended using volunteers to build the West Brattleboro Fire Station, and the suggestion was approved. The Selectboard discussed traffic hazards at Union Hill. Citizens complained about damages caused by I-91 blasting. Western Avenue was torn up for sewer installation.

One of the bigger issues in town was the debate over adding Fluoride to the water system. The Selectboard voted to install the necessary equipment at one meeting, but held a special meeting the very next day to rescind that decision and allow voters to decide. Voters said no to fluoride in the water.

The biggest issue of all, perhaps, was the debate over a regional airport proposed for Hinsdale. The Brattleboro-Hinsdale airport would have had a 3,200 foot landing strip and 3,000 foot runway. Brattleboro was asked to contribute $10,000 toward the $130,000 project, with much of the money coming from state and federal programs to increase air travel and transport. It led to a high Town Meeting turnout in 1959, and was defeated.

Robert Gannett

One person more than any other is given credit for bringing Representative Town Meeting to Brattleboro.

Robert T. Gannett was born in Milton, MA, in 1917. Robert’s mother was Mrs. Thomas Brattle Gannett, making Robert a descendent of our town’s namesake. A portrait of William Brattle hung in his family home in Milton when he was growing up and was later donated to Brooks Memorial Library.

When Gannett was about ten years old, Milton adopted a representative form of town meeting. Using this system, residents elect representatives to attend each town meeting on their behalf. In turn, those elected are expected to pay close attention to local issues in order to make informed decisions for their constituents.

The Milton way would have seemed ordinary and familiar to him as he grew up. Gannett would have seen his parents and their friends participate in the representative form of town meeting for many years.

Gannett graduated from Milton Academy and went on to Harvard for his undergraduate (1939) and law (1942) degrees. Just prior to getting the law degree, he married Sarah Alden Derby, the third daughter of Ethel Carrow Roosevelt Derby and the granddaughter of Teddy Roosevelt. She was raised in Oyster Bay, N.Y. on Long Island.

Gannett served in the Army during World War II as a major in a field artillery unit. In 1946, just 29 years of age, Gannett moved to Brattleboro with his wife. He partnered with James L. Oakes and began what would become a long legal career.

He made his entry into town life by joining Brattleboro’s Recreation board. He also had his first experiences with open town meetings in which any voter could attend.

It was in 1953 that he began down a path to change the way Brattleboro governed town business. It was in this capacity that he was elected to the Vermont House of Representatives. He began working to get the state to pass an act that would enable Brattleboro to choose an alternative to the regular town meeting to which Vermonters were accustomed. In a manner similar to Milton, MA, the act called for voting districts to be created from which to elect the representatives who would decide many town matters.

It was in 1953 that he began down a path to change the way Brattleboro governed town business. It was in this capacity that he was elected to the Vermont House of Representatives. He began working to get the state to pass an act that would enable Brattleboro to choose an alternative to the regular town meeting to which Vermonters were accustomed. In a manner similar to Milton, MA, the act called for voting districts to be created from which to elect the representatives who would decide many town matters.

During late 1950s, Gannett served with former Selectman Richard H. Sherwin, Town Clerk A. Hadley Shumway, Judge Ralph Chapman, and Ernest Gundersen on a town committee to study and report on the new form of town meeting. They drafted a report for the legislature and the Selectboard,

“Their committee report, on which Representative Gannett’s bill was based, is in such detail and is so complete that practically no spade work needs to be done,” announced the Reformer in June of 1959. The Enabling Act was passed, and he left the House that year. (Interestingly, the committee report is one document I could not find.)

Gannett’s success raises a question. Why would longtime Brattleboro residents trust a young, out-of-state lawyer to alter their form of town government? After all, he was in his 30’s for most of the time he worked on this, and was only 42 when it passed.

Could the Roosevelt connection have carried some clout? Those that knew Gannett and his wife say the family relation was never paraded, but it wasn’t a secret, either.

Gannett would have had no need to ride anyone’s coattails. Friends and news articles alike praise him. They say he was intelligent, personable, thoughtful, respectful, forthright, and bright, and that he was a sought-after lawyer because he would always win. He was known for getting bills through the legislature. It was natural for him to use his skills to help solve problems.

Without reasons to change, however, there would have been no need for Gannett to spend seven years carefully laying groundwork for a new system of governing in Brattleboro. As we’ll see, the town had a number of issues after WWII that contributed to the pressure for a change. Brattleboro was primed and ready to consider an alternative.

Gannett was in the right place at the right time, with a solution to recommend based on personal experience and lawyerly knowledge of how to make it happen.

Town Hall Is Old and Crowded

Brattleboro’s town meetings were held on the second floor of the old Town Hall, a room that could hold hundreds of people.

Brattleboro’s town meetings were held on the second floor of the old Town Hall, a room that could hold hundreds of people.

At times, it could get crowded, stuffy, and noisy. There was no elevator and no sound system for amplification. Some older residents needed to be carried up to the meetings. By all accounts, it was not a good place for such a large meeting and was frequently cited as a reason that the situation needed to change.

Gannett used this problem in his arguments for the representative form of town meeting. “If Brattleboro had a large enough meeting place for the present number of voters, the proposed change would not be necessary,” Gannett told those assembled for his informational sessions, according to The Reformer.

Most Town Meeting minutes don’t have counts of how many attended, though some news reports and counts from standing votes show that regular, open town meetings attracted at least a few hundred people. As is the case now, weather and agenda items affected attendance, with “hot” issues attracting bigger crowds. The Reformer alluded to 700 people attending the 1959 meeting regarding the airport issue, the most ballots being cast since 1936.

Interest-Driven Voters Cause Instability

One major argument against open town meeting was the need for order and stability. Electing representatives, voters were told, would eliminate instability caused by uninformed voters taking over an open town meeting to advance their personal agendas.

Former Town Manager Corwin “Corky” Elwell was quoted in a 1989 Vermont Life article “The Brattleboro Way – Is This The Future of Town Meeting?” as saying “At times it got pretty unruly. It really was a case of who could pack the meeting…” and “It was pretty easy for the proponents of an issue to get their troops there and approve whatever was needed. Of course, there was nothing illegal about it. It’s just not a very stable way to carry on a local government.”

The author of the story, Fred Stetson, wrote at the time that Brattleboro was “seeking stability and an escape from Town Meeting Day shenanigans.”

Based on a review of Town Meeting minutes going back to 1952, this perception seems to be overblown.

Minutes from Town Meetings in the 1950s are limited, but they don’t seem unusual in any way. The agendas look rather typical by today’s standard. Thirty or more agenda items are dispensed with in a matter of a few hours in most cases, and there are no records of outbursts or prolonged, painful discussions of unimportant topics.

One of the only examples that arises, oft-repeated, is that a a group of baseball lovers once called for a last minute vote in support of funds for a grandstand, which they were able to get approved. One Reformer editorial mentions that the motion came from a baseball fan and editor of the paper, that the Moderator was a fan of the Northern League Maples, and the meeting “was stacked with said fans.”

The Reformer Supports Representative Town Meeting

The local paper was a loyal supporter of Robert Gannett and Representative Town Meeting throughout the 1950s and 60s.

Mentions of Representative Town Meeting in the Reformer began in March 1953. In an editorial, they opined that Town Representative Robert Gannett would be seeking legislative approval for voting on additional polling places and representatives elected from districts for a representative town meeting. The first list of reasons for trying Representative Town Meeting were given.

At the top of the list, the Reformer argued that too few people vote, and only a handful of voters make decisions on big budget issues.

The editorial pointed to Brattleboro’s single polling place and meeting space, Town Hall, which required people to walk up two flights of stairs to a meeting that had grown too big for the space. Wouldn’t it be better to have multiple polling places around town, they suggested.

The editorial argued that letting voters elect representatives would be more fair, and would be better than adopting a city form of government. They hoped that Gannett would complete the necessary work and that representative town meeting would begin the following year, in 1954.

It took until the close of the decade before the legislative Enabling Act had passed and Brattleboro could vote for the proposed new system of governing.

The newspaper praised Gannett’s report that convinced the legislature to pass the enabling act of 1959.

In 1959, during the run-up to the town vote on representative form of government the Reformer had more editorials in favor of the change and used similar arguments. Too few people vote, they wrote, and also that Town Hall is poorly equipped to hold a regular town meeting.

A March 1960 editorial calls the regular town meeting wonderful, but also irritating, frustrating, honest, stubborn, vindictive, and confusing.

The editors told readers that if they elected representatives to go to Town Meeting for them, Brattleboro would have a more stable system of governing, and their interests as voters would be better represented by the inquisitive and civic-minded citizens they vote to attend for them.

They also ran editorials praising Gannett. In February 1960, when he decided to run against Governor Stafford for the national House of Representatives, the paper said “Certainly, in this town as well as throughout the county he deserves and will get strong support. His work in Montpelier has been marked by indefatigable work in behalf of local projects and the development of qualities of leadership which fit him for service at higher level.”

Did Brattleboro Outgrow Open Town Meeting?

The representative form of governing wasn’t entirely unusual in New England, nor was it limited to Milton. Greenfield, MA adopted a representative form of town governing in 1921 and the Reformer mentioned Greenfield in their first editorial on the subject. Other towns in Massachusetts also favored the representative town meeting, such as Athol, Adams, Amherst, South Hadley, Montague, Dedham and others of similar size. (Towns in Maine and Connecticut had adopted Representative Town Meeting as well.)

Most towns in Massachusetts, however, stayed with an open town meeting. Cities typically had mayor and council form of government.

The dividing line between city and town in Massachusetts is considered to be 12,000 residents. Less than that amount and a location is considered a town; more, and the location qualifies as a city. Brattleboro, using these definitions, would be on the edge of being too big to be a town, and just small enough to not quite be a city.

Consequently, Brattleboro in the 1950s could be seen as getting too big for an open town meeting and too small to make the jump to a mayoral system. Another, in-between option would, no doubt, have had appeal. “Voters will decide whether they have outgrown the town meeting and need a representative town meeting to handle the growing complexities of government,” said the Reformer on the day of the vote.

Most of the Milton, MA charter is almost identical to Brattleboro’s. One notable difference is that Milton has a Warrant Committee made up of 15 legal voters of the town, each serving for a year. This group informs themselves on town affairs and interests and decides the articles for the Town Meeting agenda as well as questions to be submitted to the voters. The Selectboard gives this group a draft budget by December of each year, and they in turn make recommendations to town meeting representatives.

Governing continues to evolve, by the way. In 2002, Greenfield voted to use the city model with a Mayor and Town Council.

Brattleboro’s Final Open Town Meeting, 1960

Robert Gannett held multiple public meetings in early 1960 to explain the proposed new form of governing to voters. The Reformer encouraged people to go, but reported lower than expected attendance “for such an important issue”. To those who would listen, Gannett argued that the representative form of town meeting “was the best known to secure an intelligent vote from the populace,” according to the paper.

In the lead up to the vote, the newspaper ran editorials and stories encouraging the changes. In January, 1960 they reported that “Selectmen and many other town officials are in favor of the broad new system, and so far there has been no apparent opposition.”

In March 1960, the Reformer opined: “The net result of such representative government will be to make the decisions of the town meeting those of the entire town instead of those of the few hundred who can crowd into the Community Building. It will substitute the rule of the majority for the rule of the minority, and will discourage and steam roller tactics that could, on occasion, nullify the voter’s wishes.”

The main feature, the Reformer said, will be to divide Brattleboro into four voting districts and provide elections in those districts of representatives to the annual town meeting.

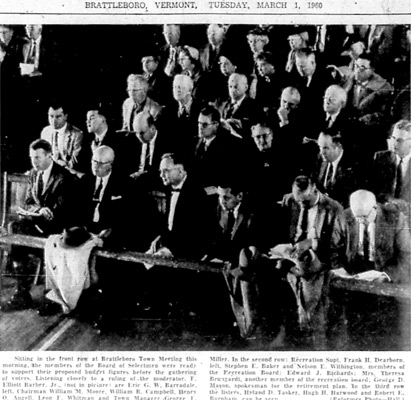

On March 1, 1960, at 9 am, Brattleboro voters assembled for what was to become their last regular town meeting. A request for a standing vote during the meeting over a contract issue recorded 255 people in the room.

On March 1, 1960, at 9 am, Brattleboro voters assembled for what was to become their last regular town meeting. A request for a standing vote during the meeting over a contract issue recorded 255 people in the room.

Article 5, “to see if the Town will approve the establishment of the Representative form of Town Meeting as provided for by No. 302 of the Acts of the 1959 General Assembly,” was on the ballot, and it was under discussion that day.

David Dunklee said that the rights of taxpayers would be diluted and assigned to the relatively few representatives of varying districts. Gannett replied that a voter would have more chance to express his views than under the current system “which is confined to the bricks and mortar of the Community Building,” and said that no other New England towns using the representative system had repealed it.

William Campbell said many people were currently disenfranchised because the Community Building cannot hold all who wish to be heard.

Virginia Hewitt agreed the present hall was too small., and that the meeting should be changed to May or June and held at Stolte Field.

The 27 articles that day included allowing the Selectboard to enter into 10 year tax stabilization agreements with new industries and a town employee retirement plan, both of which passed.

The total property and schools tax came to $10.41.5 on each dollar of the grand list, with an additional $5 tax added for old age assistance. A suggestion to combine the Recreation department with the schools was noted but not acted upon.

Discussion was “rife and sometimes heated” during the floor session, but the meeting was otherwise “routine” according to the Reformer. The meeting adjourned at 11:45 am.

Voting by ballot continued until the polls closed at 6 pm. The end result was 1,293 – 749. The traditional open town meeting in Brattleboro was no more. The Reformer proclaimed it a “convincing victory.”

The paper said it was “relatively heavy voting” for town offices, but more people had come out for the airport and fluoride votes.

The First Representative Town Meeting, 1961

Soon after the vote in favor of representative town meeting, Brattleboro got to work preparing for the new system. By September, four new voting districts had been approved by the Selectboard in accordance with the enabling act. The Reformer ran a series of articles explaining the details of the new form of government.

At the first general meeting on March 7, 1961, voters elected their new representatives. They were also asked the annual questions about beer, wine, and spirits. Ballots were counted and the day was done.

The very first Representative Town Meeting was held March 18, 1961. Of the 105 representatives elected two weeks earlier, 102 attended. (The enabling act allowed for up to 140.)

The agenda remained as it had been for regular Town Meeting, with authorization of spending, appointments, and other matters. The only significant changes were that fewer people were part of the discussion, and the meeting was held in a new location – the gymnasium at the high school was a new, larger space.

Taxes were set at $3.345 on a dollar of the Grand List. School tax was $1.917, and the BUHS share was $1.323.

Before the meeting ended, Robert Gannett made a motion to have the Selectboard set up a committee to establish rules for Representative Town Meeting, which carried. In May, Gannett, Moderator Barber, and Town Clerk A. Hadley Shumway became the committee to set rules.

The First Special Representative Town Meeting

In March 1961, minutes of the selectboard note a suggestion “that candidates for Town Meeting Representative not be allowed to take part in counting votes in their district. “ The Board of Civil Authority was tasked with taking up the issue.

Just weeks after the first Representative Town Meeting, the first special meeting of the new representatives was held. Minutes report that 115 of 119 representatives attended on April 10, 1961, a small increase from the previous meeting. They voted in favor of reconstructing the lower Main Street Plaza.

Coming Wednesday in Part II: The Reaction and Repeal of Brattleboro’s Representative Town Meeting.

Images fixed, and some thoughts a few years later

Adding a note here that I’ve fixed the broken images and the story is back to the way it should be.

I also re-read much of this (it has been a few years…) Very interesting, if I do say so myself. : )

My current view is that Brattleboro still has a problem with democracy – from requiring taxpayers to run for office to be able to have a say at Town Meeting, to disenfranchising voters by not counting “non-registered” write-in votes. If there is a roadblock, Brattleboro seems inclined to erect it. And when it is pointed out how cumbersome this is, officials tend to get defensive. (The Town Clerk wants to expand unnecessary limitations on write-in choices statewide!)

Someone brave, someday, will get a ‘return to Open Town Meeting” on the ballot. (It should have been a regular question, say, ever 10 years or so….there was no evaluation of RTM built-in.)

Bump

I bump this up again, for those who would like to know the story, and also because of recent poll results showing that a majority would like to return to open town meeting.

Bump

An annual bump so people can find this, as it is time for Town Meeting again.

Greetings to everyone coming from the links in the Vermont Research Newsletter from the Center for Research on Vermont at UVM.

Twice in 2020

This year, this story gets promoted twice due to the almost-RTM in March, and the new virtual Zoom meeting version this week.

Ironically, if Brattleboro had held an open town meeting in early March like most of the state, this special Zoom meeting would be unnecessary.

2024

Your semi-regular reminder of the history of Brattleboro’s Representative Town Meeting.

Interesting to note this year: The Charter Review Commission is having an open public meeting about whether this is the best form of government for the Town of Brattleboro.

2025 - your annual revisit to RTM

Adding to the record – we should note here that in 2024 (as a result of the meeting mentioned above, in part) the Charter Revision Commission considered asking the selectboard to put an article on the warning to allow people in town to vote on RTM. It was on the agenda then was pulled at the last moment.